• This story contains elements that some people may find triggering.

When I first met Matthew, we were both wildlife carers. I just knew him as the bloke who would come to snake training, and he rescued possums. He was great with flying foxes.

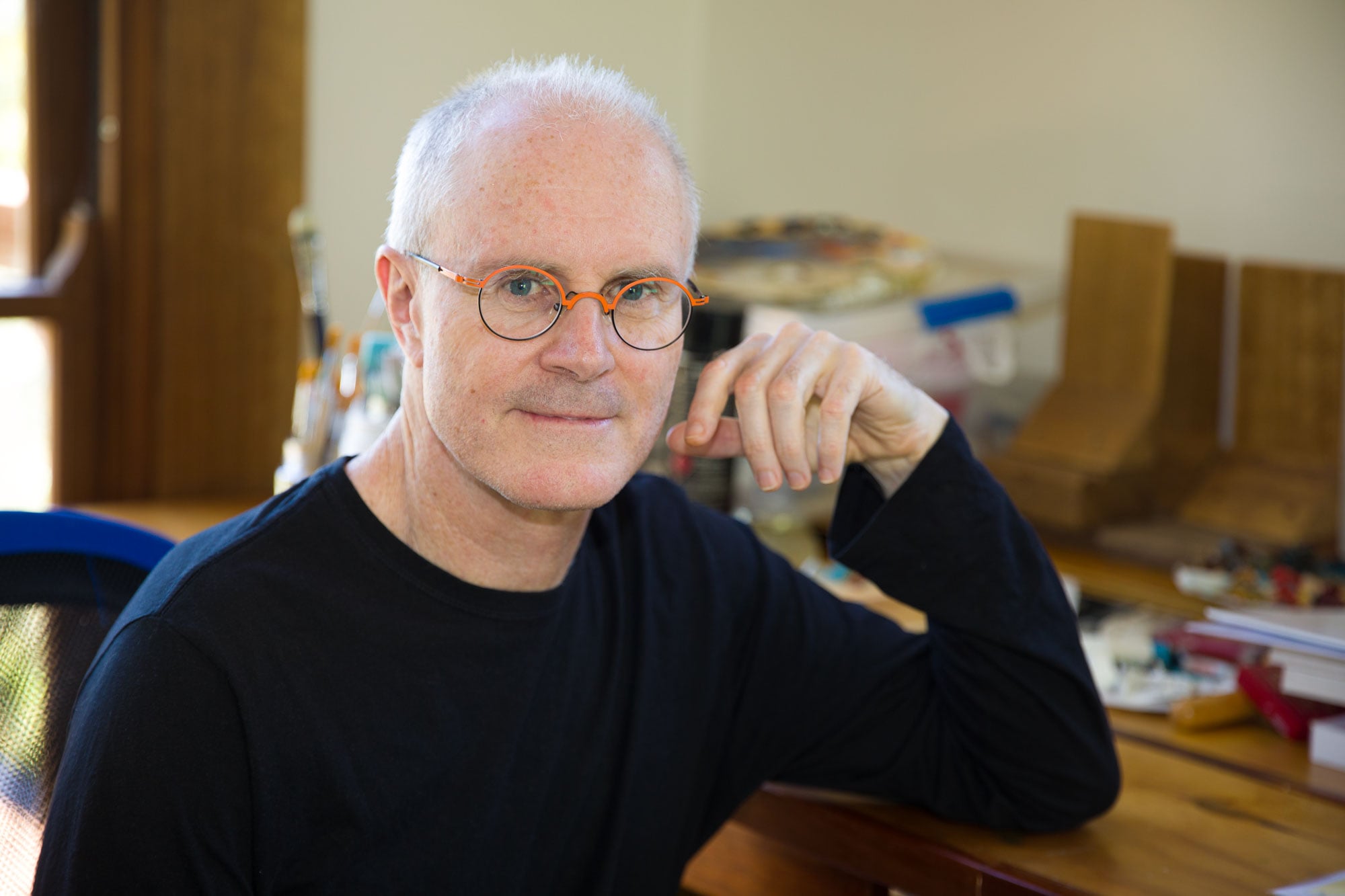

It wasn’t until later that I found out he was Matt Ottley – a multi-talented, multi-modality, multi-award-winning artist, known across half the planet.

It wasn’t until even later, when I was standing next to him in the emergency room at Mullumbimby Hospital after his first suicide attempt, and the rise and fall of his chest stopped and I screamed at the top of my voice ‘Matthew: BREATHE!’, that I found out he was a terribly distressed earthling under the weight of bipolar disorder.

He was still a wildlife carer and still a multi-hyphenated artist but he was also very ill and I was powerless to help – so was he.

Matthew had been feeling the burden of his illness grow over many years, but it wasn’t until it came to a head, and during the long recovery process which followed, that he really began to understand how ill he was.

Matthew was born in Goroka in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. In 1962 his parents were the first generation of Australians in the central highland provinces. His childhood was pretty carefree, though his home life was also fairly dysfunctional.

‘It was an amazing lifestyle,’ says Matthew. ‘We’d just wander out into the bush and play with the Melanesian kids without really understanding the privilege of that. As kids, we were witness to Melanesian Island village life before it was ever changed by the Australian incursion.’

Matthew contracted malaria at the age of six or seven which may be responsible for his synesthesia (experiencing more than one sense simultaneously) – there is also a higher incidence of it in the bipolar community.

‘That was a feature of the way I perceived the world from quite a young age,’ he says.

Trauma a trigger

Matthew was sexually assaulted when he was nine, possibly a revenge rape because of the way some Australians were treating the Melanesian people. That may have been the incident that unlocked the genes he carries for type one bipolar disorder.

‘It was about at that age I first had experiences of visual hallucinations. I saw and heard things that weren’t there, and of course, the adults didn’t believe me because I was always regarded as having a very wild imagination.’

Matthew doesn’t remember much of the next two years in New Guinea and that’s probably trauma related.

‘We came to Australia, and at 13 years of age I had what I can look back and see now as my first diagnosed episode of bipolar disorder; I had this massive high and what followed was a crash that lasted for several months. I was very severely depressed. I was taken for treatment, but that was very, very unfortunate – the first thing the doctor did was ask my mother to leave the room. And then he stripped me naked and spent the consultation examining my genitals.

‘I don’t know what passed between the doctor and my mother; once she was back in the room, she just steadfastly refused to talk about it. I kept pestering, you know, “What did the doctor say is wrong with me?” She just simply wouldn’t talk about it.’

Seeking approval

From then on, all through high school, Matthew had fairly regular episodes that were sometimes mild, and sometimes quite severe. He knew when they were coming on because he could feel his mind starting to race and he couldn’t sleep. He knew his thoughts were becoming delusional.

‘I would just literally shut myself in my bedroom and ride it out.’

Matthew says he first seriously thought of suicide when he was 17. His family wasn’t interested in talking about anything emotional. He wagged school because as the odd kid he attracted bullies – as a result he pretty much failed high school.

He attempted to follow in his father’s and uncle’s footsteps to win approval – he worked as a jackaroo and then as a ringer on cattle stations. He could ride a horse quite well and loved being alone in the bush. But he didn’t have an aptitude for that work and he was also struggling with a lot of depression, so he returned to Sydney.

Matthew studied at the Julian Ashton School of Art, but in what became a feature of his adult life, he would have a mental health episode every year. Sometimes it would be relatively mild, a few weeks of depression. At other times, it would be a short period of really manic thinking, followed by a couple of months of depression. As a consequence, he bailed out of that course after a year.

In his early twenties, he studied music composition at Wollongong University. ‘I took a folio of the music I’d been writing, and although I didn’t have school results, they let me into the course on the strength of the work that I had done. I only lasted a year in that course as well.’

What Faust Saw

He was then offered a job doing illustrations for picture books. That set him on the path to the career he has today.

‘In my early thirties, I did a book called What Faust Saw. It’s a book I’m proud of. I don’t know that it’s my best work, but it just seemed to hit a sweet spot and was translated into nine different languages. It did really well.’

On the strength of that, he was offered a handsome book deal with a publisher, and his career was set up as a children’s book author/illustrator.

It wasn’t part of the plan, but his mental health struggles made it easy just to accept work, not to have to look for it or think too much about things.

‘I discovered that you can really fudge deadlines, so I wouldn’t tell my editors that I was unwell and when I couldn’t come up with the goods by the proposed date, I’d just say I needed an extension. By that stage, they’re generally committed so they’d have to give it to you. Some of those books started getting shortlisted and winning awards.’

Highs and lows

A whole career was unfolding. It operated under its own momentum.

Matthew was also performing regularly, playing guitar with a flamenco troupe when he decided, on the spur of the moment, that he should take a person he’d just met to Bali. He booked the tickets that day, and then told her that they were going.

‘We’re going to just stay for a few days. I’d be back for my next rehearsal. But I just threw caution to the wind and ended up staying in Bali for a month having this over-the-top wild adventure. I’d be up jamming with Indonesian musicians until two in the morning, having a great old time. But the woman played me. She could see I was losing the plot. She ended up draining my bank account.

‘When we finally got back to Australia, I had totally destroyed my relationship with the flamenco band. I was really starting to crash then. It happened very quickly. I had my first serious suicide attempt.’

This is where I found Matthew – out of breath.

Not to trivialise the struggle or the cost, the 15 or so years from 2000 were a melding of art, a marriage that failed, terrific highs and unhealthy relationships, money spent on the ridiculous and the sublime, and death-defying lows.

I remember one of the many phone calls Matthew made to me from the west coast: he spent the whole conversation telling me he had to prepare for a big event the next day, all the while counting the tiles on his kitchen floor at the speed of light while he paced back and forward at the speed of insanity – all I could do was listen and hope he would come down soon.

Acknowledgement

Matthew says that if he deconstructs everything, it started with a family that felt a lot of shame around the subject of mental illness, and steadfastly refused to acknowledge it.

‘Bipolar is a progressive illness. It just got to the point where I could no longer hide it in my forties. In my mid-forties, I had my second suicide attempt. I was sectioned and put in a psych ward in Sydney.’

His treatment in that place and his recovery are nothing short of horrific, but it led to the birth of an incredible book, The Tree of Ecstasy and Unbearable Sadness.

‘While I was in ICU I had two experiences. Because of what I’d done to myself – I severely damaged my central nervous system, and I had no use of my legs – just the most basic gross motor movements of my arms. What would happen maybe once a day, I’d have a major seizure. They were really severe. My back would arch, my jaw was clenching, honestly, I thought I was going to break teeth and break bones.

‘There was a nurse who was just lovely. Once she was in the room with a male nurse – he grabbed my legs and she just threw herself on the top part of my body and said, “I’ve got you, darling. Don’t worry”. I had this unconditional care and support from these strangers.’

Other medical staff weren’t so gentle – or nice. Other friends and associates also weren’t nice. There seems to be a place in some humans where humanity stops. Some humans are vile and cruel.

‘There’s a kind of background stigma that is there constantly – since I was 13.’

Moving forward

That’s not the end of the story, the end of the trauma, nor the end of the recovery, but the seed of Matthew’s tree grew into a book that he hopes will enlighten people as to what bipolar might look like – from one man’s view.

The Tree of Ecstasy and Unbearable Sadness is a large-scale multimodal project, weaving together the worlds of literature, music, and visual art. It’s the story of one boy’s journey into mental illness. The narrative unfolds around the metaphor of a tree growing within the boy, whose flower is ecstasy and whose fruit is sadness.

Matthew attributes his current stability to his partner Tina Wilson, his psychiatrist and the ongoing care he receives from The Health Lodge in Byron Bay – but he often lives on the edge of the tipping point, and has to manage many aspects of his life to accommodate his survival, up to and including a three-day mental health prep for our very triggering interview.

Once, about 13 years ago, I asked Matthew if he would swap his incredible talent for good mental health. His answer was ‘No’.

In late November this year, I asked him the question again.

‘If I could be rid of the mental illness, but also be rid of my creativity – in light of everything that’s happened over the years, I would now say “Yes”, I would,’ he said.

‘We mustn’t at all romanticise bipolar, it’s a potentially lethal condition.

‘It has wreaked havoc in my life, destroyed friendships, and almost killed me. I would have swapped all of that for a quiet mind’.

What a beautifully written article. Thank you.

Thank you, so glad Matt’s still with us to share his wonderful talents. A very good insight.

Thank you Eve for your beautifully written article and thank you Matt for opening up and sharing some no doubt extremely difficult and very private experiences with us all. Eve’s and Matt’s co-operation is helping putting an end to the ongoing hellish stigma attached to mental health issues. I for one is very grateful for that.

Wonderful story and thank you to Matt

For your courage and immense gifts ✨

The apologetics at the beginning made me loose sympathy by the end.

Thankyou for this very interesting article…💜🪻

I found this article refreshingly honest and compassionate. Like many, I know Ottley’s work but had no idea of the creator and his journey. Thank you Eve Jeffery for introducing us. Best story this year.